Corpo Pagina

The Passio is the narration of the trial and death that the first martyrs suffered during the persecutions. A high number of Christians died because of the measures aimed against their religion by some – but not all – Roman Emperors.

At the beginning, their names and the date of their death were recorded in the Calendaria (lists of martyrs celebrated by the various Churches, each one in his date) and in the Martyrologia (collections of several Calendaria), which sometimes added further details on martyrdom.

A community needed a few elements in order for a cult to exist: a Christian killed by imperial order, his particular social role (military, deacon, adolescent, for example), the memory of the day of his death and finally the continuity of his worship in the community. All this information was recorded on materials too easily perishable and of little value to preserve them over time.

A special attention was instead paid to relics, safeguarded with the utmost possible care and often identified with the memory (relics of martyrs are placed in the churches under the altar, in a space called memoria martyrum). Thus we have no written records for many martyred saints until a late date. In the first editions of the Passiones, the stories were often written with a more concise literary style, the so-called acta, which in terms of form and content seem to reproduce the minutes of the trials against martyrs.

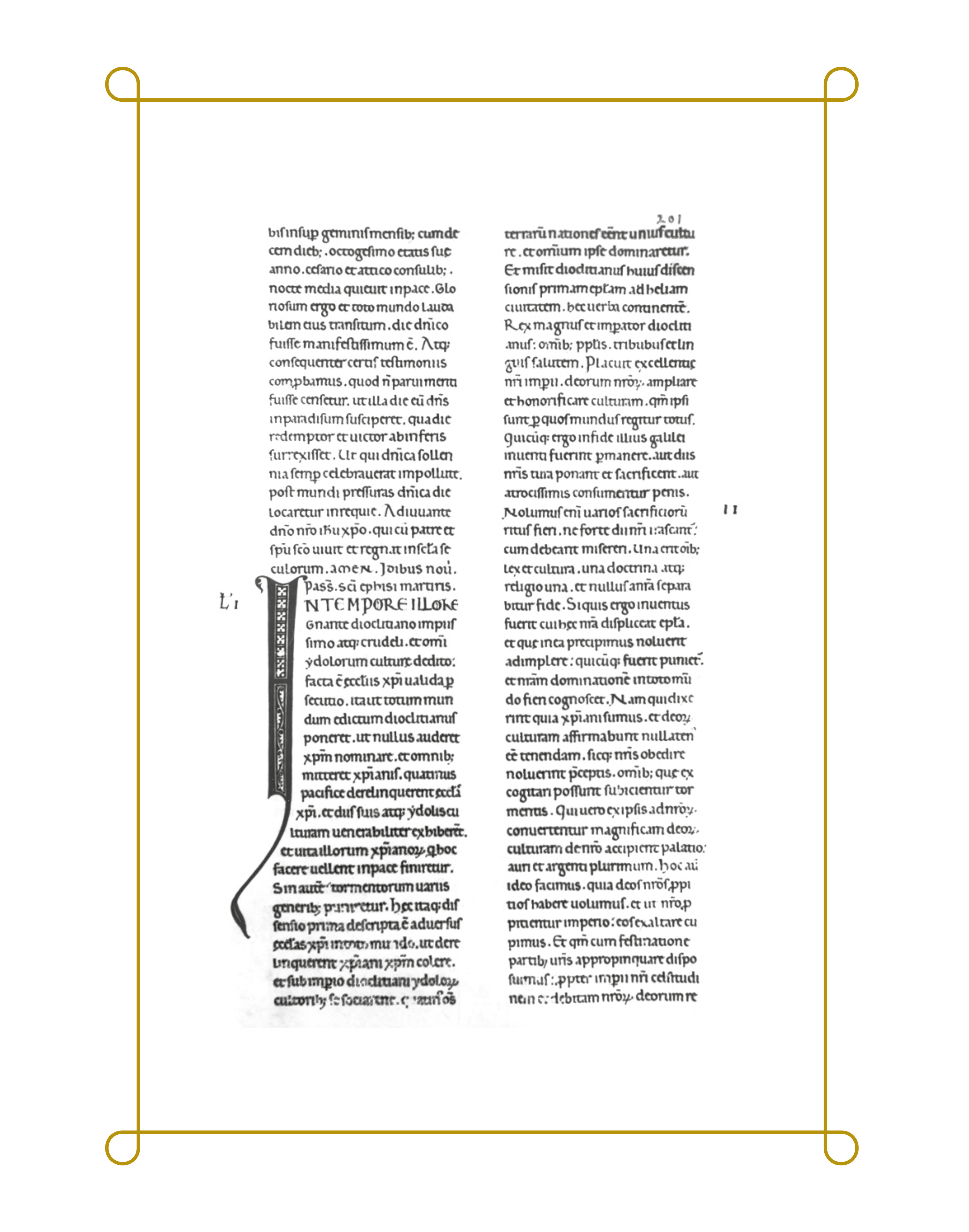

As time went on, the vicissitudes of Christian martyrs (trial, arrest, execution) were exposed in narrative form and began to be called Passiones. However, the compilers were not always able to be exhaustive. Thus, there is no trace of Ephysius in the ancient Martyrologia, but the three persecutions (the last ones in the Roman Empire) unleashed by Diocletian (early III century AD), under which Efisio died, were characterized by an unusual intensity, so many of the witnesses of the Faith were remembered only locally. The written edition of Sant’Efisio’s Passion is therefore late and attested in a manuscript kept in the Vatican Library, but coming from Pisa.

Efisio was born in Aelia Capitolina, the Roman name for Jerusalem after its refoundation by initiative of Emperor Hadrian, following the Second Jewish revolt (132-135 AD). His mother was pagan and his father was Christian. He was enlisted among Diocletian’s troops and during the journey to Southern Italy he converted to Christianity: one night, a shining cross appeared in the clouds; a voice from heaven reproached him because he was a persecutor of Christians and in the meantime announced to him his martyrdom. Sent to Sardinia to defend the interests of the Roman Empire, he was accused of infidelity and he himself told Diocletian that he had converted to the Christian faith. He was imprisoned, tortured several times and finally beheaded in Nora on the 15th of January 303.

In a genre such as hagiography (the narration of the Saints’ life), when the biographical elements of a Saint were not all available, some distinctive traits were taken from other martyrs’ lives. Two-thirds of the Efisio Passio, for example, are taken from the Passion of St. Procopius. This is a proof of the fact that some details of the Sardinian martyr’s life had been lost. This is what Réginald Grégoire wrote about this aspect: “The absence of an ancient written documentation is remedied with the drafting of adequate texts. You do not create everything from nothing; it is not true that everything is false, but it is false that everything is true. You need to elaborate a martyr’s Passio? You can use local traditions, traces of worship, the possible presence of relics and already existing martyrdom texts. Then you can trace all the editorial elements of that specific literary genre that defines the basis of each Passio: a chronological reference, a geographical location and so on”. Indeed, “in hagiography it is quite difficult to keep the distinction between true and false documents; the hagiographers do not write the false, but propose a reading of the Saint’s life which is determined by contingent needs: this form of historiography is not exact, but enhances a typological definition. The ancient concept of the document, written in Medieval times, is different from that of today! The saint is therefore “built” “.

Testo di Graziano Fois (Text by Graziano Fois)

Traduzione di Gabriele Demurtas e Giusy Pitzeri (Translation by Gabriele Demurtas and Giusy Pitzeri)